I.

It is not easy to talk about what’s happening with math in California right now. Partly this is because it involves an enormous evolving document — the California Math Framework (CMF) — that has a complicated relationship with what actually happens in schools. Partly it’s hard because the document has become caught up in the broader culture war, attracting Fox News hysteria and the attention of political operators.

But a significant part of what’s tricky is that while the CMF itself was written by committee, its presentation to the world has been dominated by Jo Boaler. The CMF itself is a complex, at times vague, grabbag of progressive math education initiatives. But the controversies surrounding it have reflected the particular idiosyncracies of its most prominent supporter. If we want to even begin to understand what exactly is happening, we have to deal with both the issues and the personality involved.

Let’s start with the CMF itself. The framework — full disclosure, I skimmed but did not read most of it — is comprehensive without being entirely coherent. As it reads right now, it basically expresses support for progressive math educational policy and pedagogy without requiring it. Here is what I saw when I skimmed it:

- The first two chapters are a mashup of UDL, NCTM’s Principles to Action, and YouCubed. Boaler’s work is cited a combination of 24 times.

- Chapters 3 and 4 read to me like a restatement of Common Core State Standards and NCTM’s standards: emphasis on sensemaking, strategies prior to memorization, multiple strategies, visuals, connections, depth of understanding over speed, emphasis on mathematical processes over content. Potentially controversial but really not much different from Common Core. Boaler is cited 8 times total.

- Chapter 5 describes CCSS/NCTM’s take on statistics but calls it “data science” and emphasizes the value of showing real data journalism to students. It also describes a culminating high school data science (don’t call it “statistics”) course. Boaler is cited twice.

- Chapters 6-8 try to organize the k-12 math curriculum around a series of big ideas. For high school, the documents basically rearticulate NCTM’s urging of schools to consider other ways of carving up the content other than Algebra 1/Geometry/Algebra 2. Boaler is cited just a handful of times.

- Chapter 9 cites Boaler 14 times and expresses concerns with tracking without really coming down against it. “Districts are at liberty to group students as they choose,” it says, but it wants to remind people to keep the pathways into higher tracks open and desegregated. I liked this chapter (which I skimmed) more than I was expecting to, even though it cites this study of Boaler’s which is really quite weak.

- Chapter 10 cites Boaler once and is basically a call for good professional development.

- I didn’t read the rest because it looked boring.

The strongest statements in this thing are all still fairly weak. In Chapter 8, the authors clearly have their hearts set against acceleration. And yet they say this: “Some students will be ready to accelerate into Algebra I or Integrated Mathematics I in eighth grade, and, where they are ready to do so successfully, this can support greater access to a broader range of advanced courses for them. At the same time, successful acceleration requires a strong mathematical foundation.”

This has all been revised several times. Its original version contained stronger language. I found this article about the revisions quite helpful — basically, the culture war language was removed in this draft, explicit support for San Francisco’s de-tracking experiments was removed and the recommendations to de-track without acceleration were softened, everything was clarified to be a recommendation and not a call for change. It’s not very surprising that people were provoked by the earlier drafts.

But now, nothing in CMF sounds particularly firm. The statements against tracking and acceleration are fairly cautious. You have no doubt what the authors think in this document — they like teaching towards big ideas, progressive pedagogy, data science, detracking, no-acceleration — but as it currently stands this document has no teeth.

So why is it still so controversial?

II.

At this point it becomes impossible not to talk about Boaler more personally. I want to stick to the facts as I understand them as much as possible, while still drawing an accurate picture.

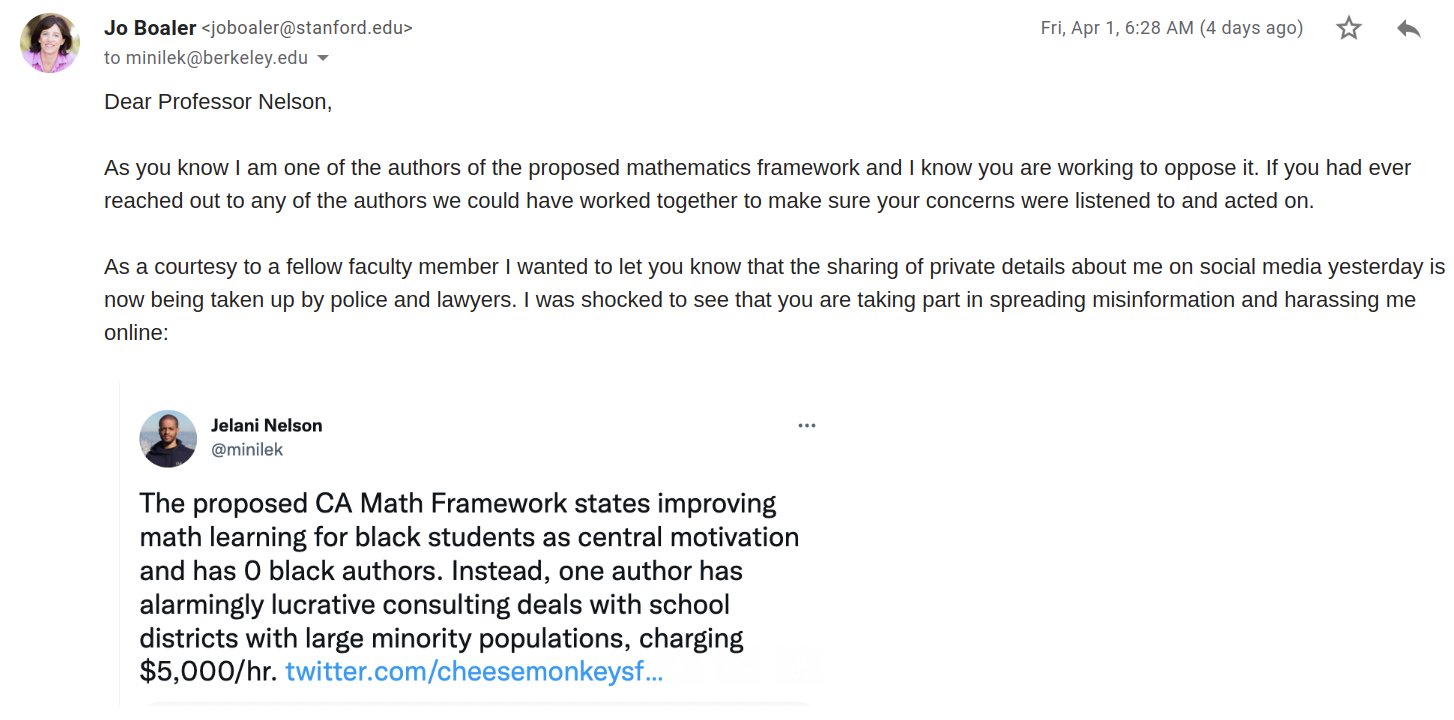

Let’s start with the emails. I have three to talk about. The first was sent to a professor of engineering and CS at Berkeley. It looks like this:

The second was sent to me by Boaler after I declined to help with a YouCubed project and explained that I had concerns with the way they handle research. (I’ve written about these concerns in “YouCubed is Sloppy About Research” and “YouCubed is More Than Sloppy About Research.”) The response I got from Boaler was that she hadn’t realized I was the author of that “awful blog post” and that she would never want to work with me.

The third email was sent to a person who I can’t name. I don’t want to give any details about the context because I don’t have permission to share any of them, but he had done something entirely inoffensive. He received a message in response from Boaler. She described him as attempting to “discredit” her. She didn’t see any value in what he had written — what was the purpose in being critical? And won’t that just direct people to go after her on Twitter? She requested that he change his writing to sound more respectful to her, and she suggested that the author had ulterior and selfish motives.

OK, on to the research.

As noted, I have described errors or sloppiness in YouCubed/Boaler’s published research. The first post described a straightforward misinterpretation of Moser’s growth mindset study. This was pointed out many times to YouCubed and they reprinted the misinterpretation many times over. (The CMF actually cites the Moser study correctly without the misinterpretation, I was stunned to see.) The second post described failures in the research studying YouCubed’s own initiatives. A third post featured a blatant inconsistency in a research article that has now been corrected without explanation.

There was also the famous Railside paper. Boaler seems to have attracted some genuine harrassment from a pair of professors who were threatened by her work. (People who witnessed this behavior but were otherwise critical of Boaler have described it to me as harrassment. Boaler’s version of the story can be found here.) The mathematicians charged that there were issues with her paper, and I’ve never given it a serious look. What I can report is that when I talk to other mathematics education researchers, they have raised their own concerns about the Railside study. My interpretation of those concerns is that they aren’t allegations of fraud. They are roughly similar to the concerns that I raised in my posts about her more recent work — that there is a kind of carelessness to them that makes them less than fully reliable.

Now, to Twitter.

I once noticed that some YouCubed tasks had been reprinted from other sources without attribution. I posted them on Twitter (somewhat melodramatically):

The response from Boaler was consistent with the perspective expressed via email — basically, why aren’t you being more supportive?

Now, back to current events.

Jelani Nelson’s posting of Boaler’s email made its way around Twitter. Boaler in response created a new website, joboaler.org. The first thing posted there was a letter in support of her against the pushback from Twitter. She soon wrote three blogposts.

The first blogpost presents a kind of origin story that has animated Boaler’s passion for her work. It’s the story of her experience of a sexist physics teacher:

There were about 15 girls and 15 boys in the class, and before the national exam everyone takes what is called “a mock exam.” I did not (as was typical for me) do a lot of studying and only got a border line pass. That was true for about 8 students, half of whom were girls and half boys. The teacher then pronounced that all the boys could take the higher-level physics exam paper and all the girls should take the lower-level paper, as although we had got the same results, it was clear that the boys had got them from real understanding and the girls had just worked very hard to get them. I was about 15 at the time and fully aware of the sexism at play. My family argued with the school and got me placed into the higher exam. I ended up getting the highest grade and I still remember the teacher climbing up the grassy bank on a hot day to mumble an apology to me, a few months later. But the damage was done and I decided against studying physics for A-levels. It would have been with the same sexist teacher. The other girls did not argue the decision and ended up with low grades in physics- as that is all that is on offer in the low exam paper

The second blog post describes her mistreatment on Twitter:

On Twitter I feel as safe as I would walking into a bear pit, completely naked and covered with honey, with a sign saying “eat me.” My feed makes if clear that anyone can write anything! I wish Twitter had fact checkers like we see during election season. Instead, people post outrageous lies, and there’s no stopping a salacious tweet from going viral, even if the claims are ridiculous. I have been subject to huge amounts of abuse and name calling, and the culture of bringing down anyone who is successful is rampant. It was Twitter where the attackers of the Framework published personal contracts with my home address. This actually violates Twitter’s rules and when I reported them, their account was locked – briefly. But others retweeted my address – and Twitter did nothing about it.

(A quick fact check on this: the content that was posted was her address in the context of a bill for her contract work for a district. The district published that bill in its public disclosures — all perfectly normal — and it was retweeted by an opponent of the CMF. Twitter says that does not break the rules of Twitter since it’s public information but that they do reserve the right to ask people to take that stuff down, to protect from potential personal harrassment. In fact they temporarily froze the account of the person who shared it and the person took down the post.)

The third blog post describes her warm feelings for a “rule-breaking woman”:

My first memory of Mrs. Marshall was her running up the stairs to our classroom, coming into the room out of breath, throwing herself against the door which she slammed behind her and panting – sharing with relief that she had just missed the head teacher (principal), who would have reprimanded her for wearing dangly earrings. I was immediately in awe of this rule breaking woman – who was so personable and friendly and different from any other maths teacher I had ever known. Then she did something even more remarkable. She told us that we would learn the calculus ideas she was teaching us by talking to each other in groups. This was my first time of discussing mathematical ideas with my friends and it gave me access to a depth of understanding I had not even known possible.

That’s where the story is up to today.

III.

So, what does it all mean?

I have no interest in psychologizing, but the facts say that Boaler sees criticism as personally discrediting and she does not like it. Her research — and at times YouCubed’s publications — have made errors or failed to live up to the highest standards. It has been difficult to get Boaler or YouCubed to correct those errors.

In the context of CMF, she did not write the entire document. Some of the chapters more clearly show her influence than others. Either way, in its current draft form the document as written seems entirely unthreatening to me. (I lack the on-the-ground knowledge of how such a document would be received and implemented in California’s schools, and defer to others on this matter!)

But as a public advocate for CMF, Boaler is prone to see criticism as threatening to the project and will escalate conflicts rather than engage with criticism.

My sense is that as CMF is gaining more attention that people are having a hard time disconnecting Boaler’s public advocacy from CMF itself. Even if there are parts of the CMF that I disagree with, I’m more inclined to shrug than anything else. It seems extremely unlikely to me that this document in its current form will make much of a difference in the daily lives of students, even if passed. (But again I defer to people more familiar with California’s school politics than I am! It would be terrific if someone would report on this aspect of CMF!)

That said, Boaler’s actions seem to fairly invite scrutiny of the document itself. It’s reasonable to ask if those citations of research have any weight. It’s reasonable to ask how fair the document is being when it talks about how neuroscience and other forms of research support what the CMF is calling for.

Most of all, though, I want to call into question this whole way of doing business. Who thought that this — getting an edu celeb who takes criticism poorly to create and then promote an enormous franken-doc containing every controversial idea in math education — would be a good idea? This is not how progress in math education is made, I hope everyone can now plainly see. Ours is a field of millions of teachers who actually decide what is going to happen in classrooms and countless more students and families who set the stage for those decisions. There is no real room for combativeness in education. Teaching isn’t the sort of where you can defeat your enemies. They’re still your enemies, and they’re not defeated! They’re there, and you need them.

There are countless ways to promote equity that look nothing like this. It would be quieter and less attention-seeking. The entire standards-writing project has produced basically no fruits over the past few decades. It’s time to stop looking for warriors and get to work.