I.

I’ve been puzzled by reports that some teachers and their unions, even after being fully vaccinated, are reluctant to return to in-person teaching. (For example, in Portland.)

My wife and I are both teachers. We’ve both been teaching in-person all year, and recently got our second shots. Over dinner a few nights ago we were hashing this out. If you’re vaccinated, why wouldn’t you want to come back? If we take these teachers/unions at their word, it’s all about lingering safety concerns. Or is it just trying to hold on to the “perk” of working from home for a bit longer?

I bumped into an elementary teacher friend yesterday who I admire a great deal. She has been fully vaccinated and I know she cares a lot for her students. She understands that vaccines are effective. She works hard for kids. Still, she’s praying that they don’t return in-person. And she even said she has colleagues who are afraid of getting their shots, for fear that they will have to come back to schools. This is seemingly crazy — sure, ventilation is awful in a lot of places, but are they less safe than not being vaccinated?

But after talking to my friend, I think I understand the situation much better: teachers are scared of hybrid teaching. There are safety concerns, but they aren’t the primary source of anxiety. After talking with teachers on twitter about this last night, I think I got some confirmation of this line of thought. And while this theory has the downside of not taking union rhetoric at face value, it does have the benefit of being an entirely reasonable concern about working conditions. It is not a crazy thing for teachers or their unions to worry about.

II.

For people who either aren’t teaching or aren’t deeply thinking about this, they might be baffled as to why there’s hybrid teaching at all. Just let kids back — all of them! And teachers will teach their kids, and not have to worry about Zoom or Google Classroom or anything.

There are two big things that make it difficult, if not technically impossible, to bring every kid back in person:

- Parental choice

- CDC requirements

The first challenge is parental choice. At this point, anyone paying attention knows that a large percentage of parents don’t want to send their kids back to physical school buildings, and that disproportionately it is white parents who are eager to get their kids in-person. The exact number of parents will vary from place to place. The point is that it doesn’t take that many parents to present school systems with a problem: what do you do with kids who aren’t coming in to school?

Schools have a few different ways to handle this situation. The idea of matching fully-online students and fully-online teachers seems reasonable, and some places have managed to pull that off it seems. Most places haven’t done this though. Why not? I think because it necessarily means that kids are not in contact with their friends from school — they are instead placed in new classrooms with teachers who may not even be from the school. (This only works if you have a large pool of fully online teachers, so it has to happen at the district level.)

The other thing is that this is expensive, especially since every in-person teacher needs to have the capacity to teach online simultaneously anyway. Everyone who teaches in-person has had students drifting in and out of the computer this year as they are quarantined, sick, tired, or because their parents are taking them to visit family or whatever. If you’re building that capacity in classrooms anyway, it’s hard to make the case that you should also spend money to create a dedicated online teacher corp. (Brookline, MA schools had a Remote Teaching Academy this year, but are phasing it out next year because of cost.)

As long as a large percentage of parents are choosing not to send their children in-person, teachers will then be forced to teach students simultaneously online and in-person. Which (as we’ll get to soon) hardcore sucks.

The other factor is CDC requirements. Now it’s important to note that states don’t have to follow the CDC. Florida is not. If you ignore what the CDC says, then what the CDC says is not a problem. Due to a variety of American pathologies, this is more likely to happen in Republican-governed states than in Democrat ones.

But if you do follow CDC requirements, then schools have a problem. Which is that you can’t fit all the kids in school, and it’s not even close. Again, there are various more or less expensive and reasonable ways of handling this. But the point is that if all kids were in school, then all kids couldn’t sit six feet apart, and the CDC says that they have to do this. This necessarily involves complicated scheduling that dictates which kids can be in school on a given day.

How do you handle the teaching side of this? Some schools give students dedicated online and in-person teachers for a given day. But it seems to me that most places are not doing this[citation needed]. Instead most places are asking all teachers — even and especially those who come in in-person — to do either of these two things:

- Create a day full of activities for students who are in-person as well as a slate of online activities that students can do at home on that day.

- Asking teachers to simultaneously teach students in-person and online at the same time.

Both of these are a lot of work, and simultaneously teaching both on a computer and in a classroom is especially a lot more work. My main point above is that if schools ask teachers to come back, then they will in almost all cases be asked to do some version of hybrid teaching — either managing multiple cohorts on a given day or teaching simultaneously online and in-person.

III.

These forms of “hybrid” or “simultaneous” or “concurrent” teaching all suck, and they are all more or less frustrating, and they are certainly asking teachers to do a great deal more work. And as such, they are completely valid concerns for teachers to raise about returning to school, whether or not they have been vaccinated.

Speaking personally on this is tricky for me. I currently teach at a relatively wealthy private school where class sizes are in the teens, not the twenties or (god help me) thirties. I have been going in in-person since the start of the year. (Biking from Washington Heights to Brooklyn earlier, now that I’m vaccinated I’ve been back on the subway.) The school schedule at my place is fairly complicated, but because of parents keeping their kids home I’ve been teaching simultaneously online and in-person.

And it’s very hard but here’s what I’ll say — I only feel dumb about it when very few kids are at school. When most kids are in the classroom and a few are online, well, it’s not more effective for the kids who are online. But at least I feel like my presence at school is worthwhile. I can more easily help kids with things, I can keep an eye on everyone, and more important it feels like there’s a real social environment. Yeah, it’s really hard for the kids who are online and it’s even harder to pay attention to them.

I think this distinction is maybe missed on people? Hybrid with a few kids in-person is really, really hard. Hybrid with a few kids online is manageable.

I know of lots of teachers who are facing situations where three or four kids are coming into their physical classroom while they have many more students Zooming in online. That’s a recipe for frustration. That feels like you might as well have everyone stay at home, since you’re basically teaching online anyway — but you also have to watch these kids. (Especially elementary school teachers, since you’re really supposed to be in charge of these kids but you can’t! It can feel like impossible babysitting while also doing your job.)

Teachers are being asked to do this now. And so it really would be reasonable for teachers to worry about this, at least until the CDC relaxes restrictions (perhaps because cases have fallen), until more parents are comfortable sending their kids into school, until weather is warmer and outdoor spaces can be used, or until a more robust promise can be secured that bad teaching that is double the work won’t be required.

In many places, this won’t happen until vaccines are widely available not just to teachers but to all adults. That means that a lot of places should realistically be aiming to open in the fall, not this spring.

IV.

I’m not trying to be totally dismissive to the safety concerns — like I said, I was nervous about the subway earlier this year, and actually my three-year old caught asymptomatic Covid from her preschool teacher (thankfully vaccines work!) — but I think once teachers have been vaccinated the situation really should be quite different.

Vaccines are never 100% effective, but science is starting to come in, and it looks like (as expected, honestly) the vaccines take a HUGE bite out of transmission. You are well protected not just from severe Covid but from any Covid symptoms. And if you do get infected, there is a huge reduction in how likely you are to develop symptoms. And then there is a huge reduction in your ability to transmit the disease to others, even if you are infected.

I don’t think these are additive … this means that ~90% of transmission is reduced once you have been fully vaccinated with one of these mRNA vaccines. In other words, when you are fully vaccinated you are about 10 times safer to those around you than you were before.

There are risks that you could give Covid to somebody else even when you’re vaccinated — a child, a loved one, or an elderly parent. But once you’re vaccinated it gets much safer. Here’s a reasonable way to think about this I think: once cases are down low enough that you aren’t 10 times more likely to get Covid at school than you are just going about your daily business, then you should be OK with the risks you pose to others.

I have also heard teachers mention concerns about kids and Covid, since kids aren’t getting vaccinated now. It’s true, but there’s a good reason that vaccines weren’t tested on kids yet: kids don’t really need a Covid vaccine. The risks to kids are very small compared to the risks of things that kids get every winter.

Normal, seasonal flu is a good comparison. “It’s just the flu” was a dismissive thing that people said last March about Covid, meaning i.e. Covid is not as bad as people are saying. But when it comes to kids, “it’s just the flu” is wrong in the opposite direction — Covid is not anywhere as dangerous for kids as the flu.

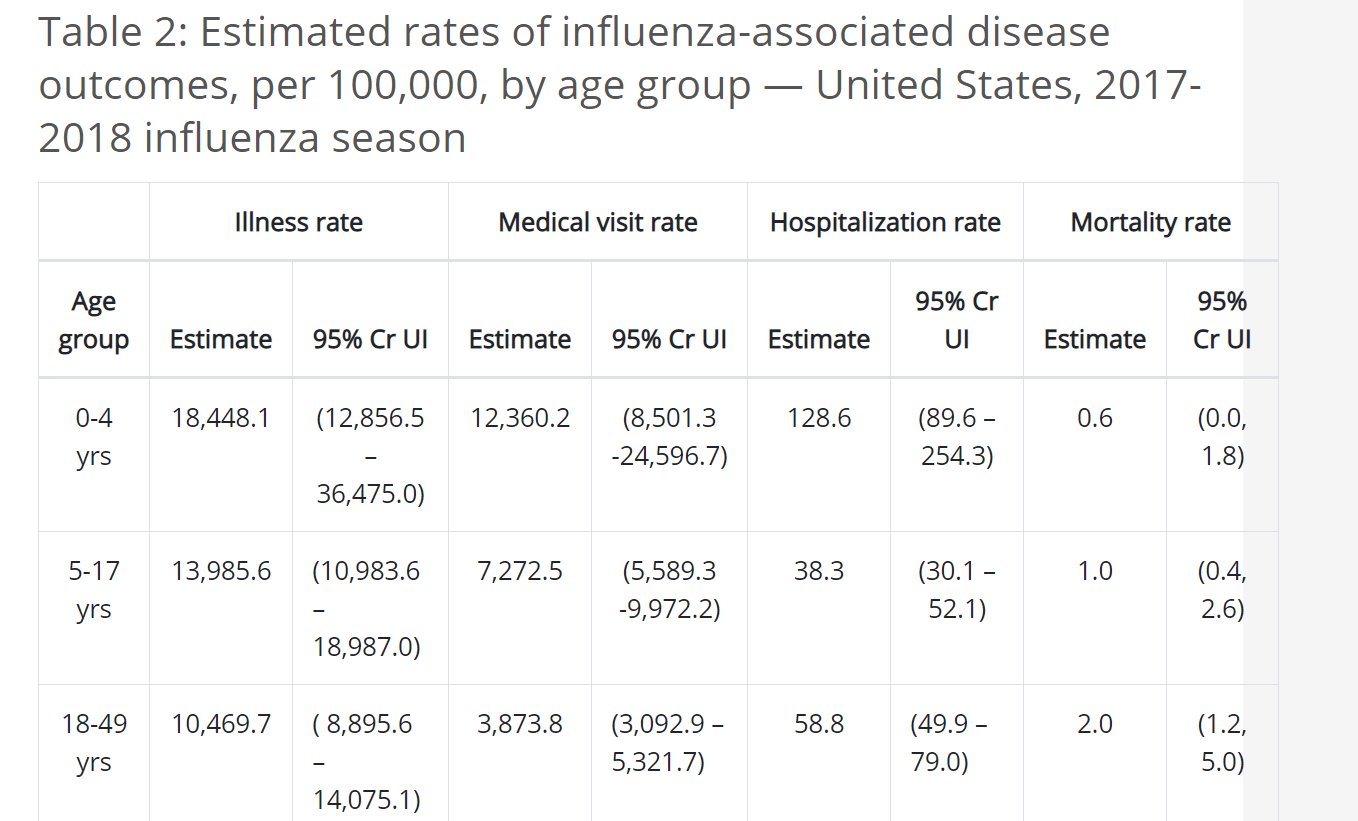

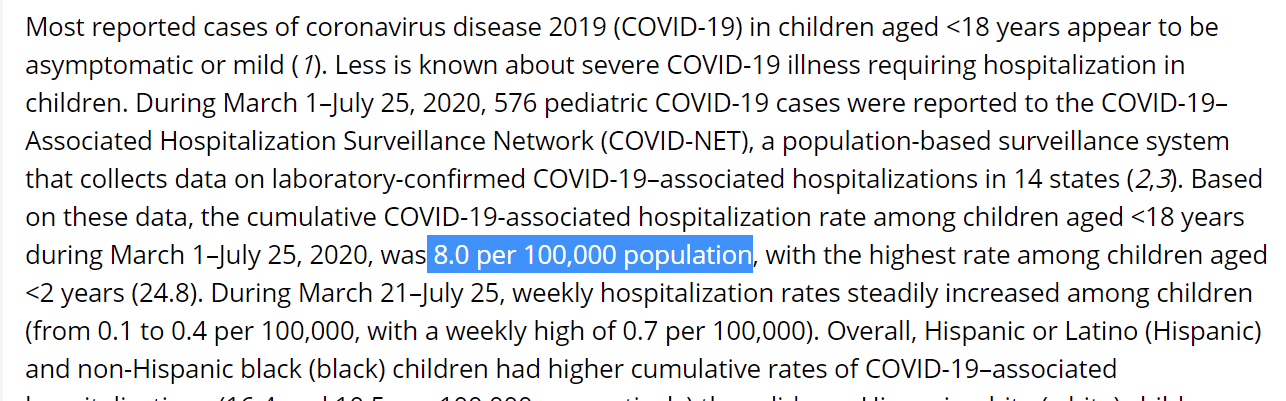

According to the CDC for kids 5-17 there are about 38 hospitalizations per 100000 kids who get the flu. But for Covid that number is more like 8 per 100000.

It is reasonable to be concerned that schools will contribute to the overall spread in a community. This is the issue that has been discussed endlessly throughout the pandemic and I find myself with absolutely no energy for it. (I think Matt Barnum has done a great job sifting through it all while keeping everyone honest.)

My point is this: if you’re concerned about safety, I think the only thing you should be worried about is whether keeping schools open will contribute to overall spread of the disease to adults. And if this is your main concern, you should no longer be very worried about this once either cases are very low or once all adults have access to a vaccine that will protect them in the case of infection. That will probably happen by the summer, so I think that all teachers should be supportive of a return to schools this fall.

V.

To sum up:

- I think the most likely explanation for teachers/unions not wanting to come to schools even after vaccination is for fear of hybrid learning.

- Hybrid learning is in fact a natural consequence of having in-person learning, at least this spring, because of parents choosing to keep kids home and CDC requirements.

- Hybrid learning in fact does suck for all involved, and it typically creates far more work for teachers — making this a legitimate concern for unions.

- Hybrid learning particularly sucks in the situation where a few kids are in physical school but most are online. That’s a recipe for intense teacher frustration.

- While in general I think post-vaccines the safety concerns aren’t a big deal, they really shouldn’t be a concern at all once all adults have access to the vaccine.

I wanted to write all this up for a few reasons. The first is to lay out why I think teachers have some legitimate grievances about the return to in-person learning, even post-vaccination.

A second reason is to make clear that parental choices and CDC requirements are a major obstacle to having every kid back in school buildings. And in fact in places where parents are enthusiastic about getting their kids in buildings and states are enthusiastic about making fun of the CDC requirements that is happening — see Florida and Texas and others.

Another is to explain why I’m still extremely optimistic that school in the fall will be pretty much in-person. The safety concerns will almost certainly be reduced as cases plummet and every adult has access to effective vaccines. Science about reductions in transmission will get firmed up and popularized. And even if a certain amount of hybrid is necessary, I think it can be the less annoying kind — the kind where a few kids whose parents aren’t ready to send them back Zoom in to class, with most students present in person.

I’m also more optimistic about the possibility of fully online academies working in the fall. At that point, parents who aren’t sending their kids might be just those in extenuating circumstances and would be willing to “switch schools” to a fully online experience. And the costs could be more manageable with more students in-person. And I think as cases drop the CDC regulations will be more clearly in favor of school even if kids can’t be six feet apart. (Someone told me online that they might already be OK with that? I haven’t read the document carefully.)

But finally this is a note to teachers and unions: just explain the situation with hybrid. Parents will get it. Parents appreciate what we do for kids, and they know we work hard. If the concerns are about hybrid learning, there is a way to communicate that it’s twice the work for half the benefit, as a teacher put it to me. The safety concerns come off as vague and unconvincing. (“It just feels kind of icky,” a teacher says in this article.)

Whereas the troubles with hybrid learning are quite clearer and easy to point to. If the real concerns are with hybrid let’s talk about that, because the concerns about increased workload with reduced benefits have the benefit of being absolutely true.

P.S. I think this piece is broadly connected to this post of mine from a few months ago reporting on some teacher polling.